Twenty floors up, midday, and Anita was feeling too dizzy to continue. Hovering between heaven and earth was disorienting. The ground below widened on all sides, the world curving beneath her. She could already see the horizon on all sides of her. Beyond and above her lay an ever-expanding infinity. Isolated from everything else, she had nothing with her but the howling of the winds and the monumental tower that stood equably beside her. The rope that was the only thing real to her touch swayed on and on in the clashing of winds.

On this level, she noticed a matrix of cuboids—housing apartments. It is said that this floor was constructed to signify the beginning of a life unventured. Inspired by the egg crate design of French architect Belara Leroux, these structures suggested the god-like egos possessed by children. Their chaotic arrangement awakened a great depression in those who lived here, making the level earn the nickname “Floor of Despair.” It was paradoxical that a work of art that symbolized the beginning of life revealed the fragility of life as well.

Already, the level hosted a new variety of occupant: plant life. Trees and vines sprouted throughout the floor, making the inside appear like a lush forest. Some of the growths breached the tower’s matrix casing and took root on the side of the building. A shower of yellow balete leaves peppered Anita as she climbed further and further upwards.

What came as a surprise to her, however, was the haze of what she thought was snow. But then she realized that it was ash. She couldn’t tell where it was coming from until she saw a glowing cigar that seemed to be floating on a branch of a very large balete tree.

“Is anyone there? I can see the glowing end of your cigar.”

A disembodied voice answered her. “You are very beautiful.”

“Thank you.”

“Where are you going?”

“Up.”

“What is your name?”

“Manorot. My name is Manorot where I come from.”

“You are very beautiful, Manorot. But why are you climbing up your rope? Why, if you were any closer and if you were any less beautiful, I would push you off and spin your rope to make you fall. You would then fall all the way to the ground and your skull would crack open. This is a very dangerous place filled with dangerous people. Including myself.”

“I am searching for the last diwata. It is my father’s hope that I find her.”

“The last diwata is dead.”

“How come I cannot see you?”

“For the simple reason that I do not wish that you see me. Such is the power of choice.”

“Then you are kapre, shadow giant of the trees, monolith of Balagtas, murmurer of WoodSpeak. The guardians and watchers of the ever-present crossroads we call choice.”

“Yes. I am kapre.”

“Then as per your own personal doctrine, you should not lay a hand on me, and you should let me pass. Furthermore, you should choose to let me see you.”

“What makes you think that I should do such a thing?”

“Clearly, you have fallen in love with me. Twice you have professed my beauty. You revealed that you would not kill me or trick me. You are in love yet you do not admit it nor do you allow me to see you. If you wish to go on without appearance, then let the kapre be cursed with choice-less-ness, that they be forever bound by fear. Such is the fate of those without choice.”

In that instant, the kapre revealed itself. A hulking figure bound with what looked like layers of black muscle, it seemed to grasp the entire tree it stood in. The creature watched her with glass eyes. A single loincloth was draped over its hips in a nonchalant fashion. In its mouth was an immense and very fat cigar that smelled of lilies, ripe mangoes, and soft grass.

“Correct, Manorot. It is indeed my personal doctrine that once I have been smitten by love, I should let my beloved see me. Furthermore, you have the right to continue on without hindrance.”

Anita nodded and continued her climb. “Thank you.”

“Not yet! You are correct that I have indeed fallen in love with you. However, because of my love for you, I am obliged to follow you on your journey upwards, to protect you from the dangers you face, and to keep you entertained lest you succumb to misery and despair. Though it is not the personal doctrine of the kapre, it is the universal doctrine of love. And I, a creature of choice, have chosen to love and to obey its rules.”

Anita smiled and held her hand out for the kapre to take hold of. “What is your name, kapre?”

“Ontok.”

“Okay, Ontok. Thank you. You may follow me upwards.”

“And what of you, madam? What of your love?”

The young girl watched as the kapre leaped from the side of the building and caught hold of the rope. Its face pleaded for an answer.

“My love is mine to give and mine alone. I have no personal doctrine to follow and no reason to love you as of yet. But give it time. You’re charming enough as it is. The choice, however, will always be mine.”

And the two ventured higher up the tower.

Come nightfall, the two made it to a section of the tower that appeared unfinished. It lay open like a fresh, dirty wound while bamboo scaffolding held the entire floor together. But in actuality, its unfinished quality was by design. That is why the floor became so popular. It represented the inchoate nature of adolescence. Some renowned bamboo structures found in the section form the shape of the chains of Bernardo Carpio, the smile of Pilandok, the uncharacteristic fist of young Marcelo de la Rosa, and the two pointed fingers of Bathala—all figures and symbols that represent coming of age. And tonight, no one seemed to be there.

“I would have expected this area to be occupied,” Anita said. “There were rumors that the building had reached over-capacity despite its height. A waste of space, then.”

Ontok took a pile of leftover scaffolding and propped the bamboo to form a lean-to campfire. With his bare hands, he cracked open one of the bamboos slits. With his nails, the giant scraped piece after piece of bamboo shavings. After he assembled the shavings on a piece of excess wood and rubbed two other pieces together, friction did its work and smoke began to appear. In mere moments, a fire roared.

“The building is indeed completely occupied,” answered the kapre much later on. “Even now we are being watched. But as long as I am here, they will not touch you.”

“Who or what is watching us?”

Ontok moved around, inspecting pieces of bamboo poles with a certain scrutiny Anita could not understand. At last, he came across the pole he was looking for, one that was incredibly rotten and foul-smelling. The giant broke off three sections of it and put them in the fire. Even from where she was sitting, Anita smelled the most revolting of odors.

“Inside,” said Ontok as he pointed to the burning wood. “Inside the bamboo they are watching us. Batibat. Waker of children’s dreams, the breath-takers, the haunted, and the upholder of the one ancient thing placed before us before any choice or action—expectation. They reside within bamboo, sleeping. And they are watching us now for we have trespassed into their territory and it is said that those who trespass suffer indescribable nightmares and die in their sleep.”

Anita gazed all around her, listening to the creaking bamboo scaffolding sway in the wind. The eyes were unseen but felt.

“Then why are we burning them?”

The giant shifted the segments of bamboo in the fire so the other parts of the shoot were heated. “The meat of the batibat is said to be of much nutritional value. Only the truly desperate seek its taste. And strangely enough, their flesh has no one taste. But it is not truly wise to eat them for even within our bellies, they will try and destroy us. That is why I am roasting them alive. Needless to say, we have already incurred their wrath.”

Ontok took one bamboo segment that had blackened at the heart and cracked it open like an egg. What slid out were a thick green liquid and a lump of flesh and bone about the size of an infant. The skin was decayed and black. The creature’s eyes were hollow. The face was that of an old and dying woman. The fangs were sharp. And with his large fingers, the giant broke off the feet and handed them to Anita.

“Be wary of the taste. Expect nothing and you will not be harmed. Eat to celebrate life and to prepare for the challenges of tomorrow.”

And the two ate.

After three more of the batibat, they were full and stopped. The two decided to stay awake for the remainder of the night since sleep was the realm of the batibat’s nightmares. And so they conversed throughout the night to keep themselves alert.

At one point, Anita, after staring at the structure that surrounded her, asked a question of great significance: “Why was this building built? What purpose does the Amando Flores Building represent?” There is no record of an answer from Ontok. We can speculate, however, at one possible answer, a reasonable one put together not long before my time by the historians, archaeologists, and other scholars who studied Amando Flores and his work.

The building, though not the tallest in the world (only the 34th according to Karasa’s magisterial Book of Buildings), is the epitome of human ingenuity and design. Every facet—from the hexagonal base to the lack of elevators—is a result not of intention but of a compulsion that stirred in the engineers’ and architects’ minds. This compulsion was spurred by the sheer brilliance of Amando Flores’s vision: to create a structure that represented the overall capacity of Philippine intelligence. The building was created to test the limits of Philippine effort and ingenuity. And so, level was built on top of level with no central architectural hold or skeleton, no preconceived design. And with every level added came a new perspective into the strength and will of a nation. Construction stopped the moment a height that could no longer support the entire tower was reached. It was not a pyramid designed to house a king or a commercial skyscraper made to house large corporations. It was unique because it was a building created with no particular end in mind. In a world where everything is thoroughly planned out to the last detail and the power of creative revelation is found only in art, what other structure was ever created with the end only realized in the end?

The building, after its inauguration, became the living testament to the power of man and the symbol of Philippine superiority. But like all things created by people, it was left behind. The economy had crashed. The nation was falling apart. The building was abandoned.

Come morning the next day, the two resumed their climbing. Soon enough, they were in the final stretch, and Anita knew it because what lay ahead of her was a dense cloud cover, impenetrable by any kind of light.

“We have to climb faster,” said Anita.

“Why?”

“I remember the legends. The manananggal dwell in these high places. Hanging onto this rope, we are defenseless. And the building holds no sanctuary nor does it allow us any surface to grab hold of. If we are to reach the top unharmed, we must get there before the manananggal reach us. With their ability to fly, they will not stop to pluck us off and kill us.”

The building, at this new height, grew to menacing proportions. One of the final levels was made of pure glass smoothed so finely and so precisely that it looked like a single solid structure carved out of a giant block of ice. Inside it was a complex system of gears and cogs that moved with autonomy. Fifteen clocks were visible to anyone looking in from outside. In each clock was a timer that counted the number of seconds, minutes, hours, and days a person had lived. It was said that every person would see a different timer. It was an effect called Planar Induction discovered by the Chinese scientist Benedict Wong. To the handful of people who had caught sight of it, it brought only madness and disappointment.

“Something is following us,” said Ontok. “We have to hurry, Manorot. They are almost within reach.”

“Don’t worry, Ontok. I can see the top of the building.”

And it was true. Just as Anita predicted, the cloud cover gave way and the summit shone in the early morning light. And right beside it, at the end of their rope, was Arthur Kadampog’s butterfly kite riding the winds in a great display of beauty and style. There was only one problem.

“The kite doesn’t reach all the way to the top!”

Had Anita paused to think why exactly that was so, she would have realized that Ontok, being a giant and a heavy one at that, was placing additional weight on a kite intended to carry Anita and Anita alone. With the giant’s mass added onto the rope, the kite was pulled down and the summit that had seemed so close now was unreachable, unless someone got off.

The reason Anita could not think of such things just then was that two large and bleak shapes appeared from beneath the clouds. Both were winged half-bodies, one of which grabbed hold of Ontok. The two creatures wrestled violently as Anita hung on for dear life, hoping fiercely that the rope they held wouldn’t break. The other creature, noticing her peril, circled her and laughed from its distance. Anita climbed higher until the rope ended and all that was left was the kite.

“When I saw the kite rising,” said the manananggal, “I thought the man who had taken the murder I had so rightfully committed had returned. I can see now that you are not that man. But as I see you flesh to flesh and smell the scent of your skin, I have marked you as my equal and my enemy. And on this day of reckoning, one of us is destined to plummet from the skies.”

“Manananggal!” screamed Anita against the wind. “Harbinger of death! Killer of the unborn child! Leave us alone!”

The creature of death flew at her and whipped at her with every pass. Frightened and scared for her life, with her back against her father’s creation, she felt it impossible to hang onto the kite. Below her, the earth seemed so far away. Only death would grant her peace.

But Ontok, who was still bound by the universal doctrine of love, caught up to her and grabbed hold of both malevolent creatures, one in each hand. And with one bite of his teeth, the rope broke. The three shadowy shapes fell and disappeared into the cloud cover below.

Anita, still clinging to the kite in horror, could do nothing as the sudden release of weight allowed the kite to soar high into the heavens. She rose so high that she flew past the peak of the tower. And she kept on going.

And as this happened, a strange metamorphosis began to take place. The creation that Anita had once thought of as a kite began to fuse with the skin of her back. She began to feel the kite as part of her, not something separate. Its butterfly shape supported her perfectly. She felt complete, a sense of wholeness. No longer bound by the wind, she was in complete control of her universe. The kite had become what they were before they were removed from her back by her father when she was born.

The tale ends there.

People have often wondered if, in fact, Anita had found her mother or what was left of her when she flew by the top of the tower or if there was nothing there. Whichever the case, the point is moot. How long Anita lived from then on, no one knows. To this day people still wonder if she’s still alive, flying beyond and above the tower. What we do know is that every now and then, it rains yellow balete leaves and the smell of cooked batibat fills the air. It is a reminder to people, like my dwarf friend Ilik, that someone is watching over them from the skies. She watches over them because she has grown to love those of the tower—a love she chose to give to the man who gave his life for her.

Matthew Jacob F. Ramos is a college student majoring in both creative writing and information design. Jake writes both science fiction and fantasy with strong local themes. “The Tower and the Kite” is his first published story.

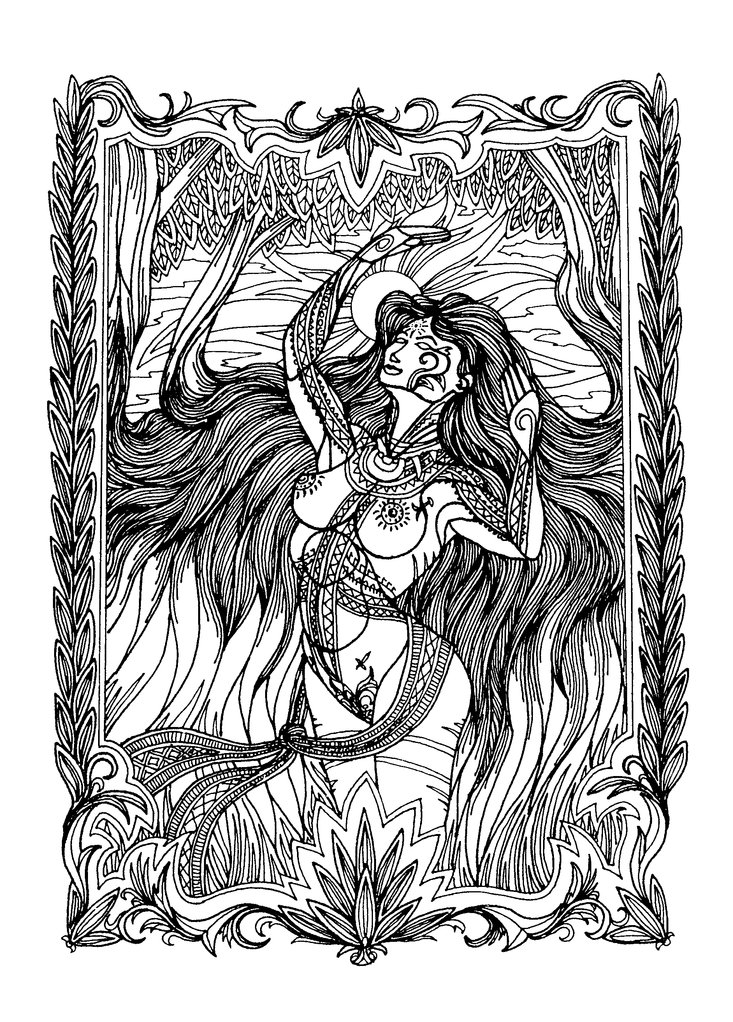

The above illustration of a diwata is by John Paul “Lakan” Olivares (used with his permission). John chooses to go by the moniker “Lakan”, an ancient word meaning “warrior chieftain”, and which is from his people, the Tagalog (“Taga” or from and “Ilog” or river, which means people of the river). To read more about him and to see his other pieces, click here.