Yna had arrived at Canterbury the next day the most determined she had ever been. She had gotten up from bed far earlier than Jobeth’s early morning nudgings; she had munched on her customary Froot Loops-Honey Stars combination to a purposeful, military rhythm; and she had alighted from the school service for the very first time with her chin held up high. She had spent the rest of the night pondering rigorously, and had absolutely no clue yet as to how she could bring Francesca to hurtle into a speeding auto, but she still knew she’d find a way. If she wanted something to happen, it would. Did action heroes cling to itineraries? Did they overthink strategies and stick to strict and unwavering protocol? No, they did not. Ploys like these unfurled best under pressure at the eleventh hour in the nick of time. She believed, despite everything, that there was justice in this world, and that vengeance for Lola Monina must be a thing of nature, spontaneous. Things would just click into place, she assured herself as she shuffled towards the Grade 4 wing. She could feel it. She could really, truly, really truly feel it.

Yna had arrived at Canterbury the next day the most determined she had ever been. She had gotten up from bed far earlier than Jobeth’s early morning nudgings; she had munched on her customary Froot Loops-Honey Stars combination to a purposeful, military rhythm; and she had alighted from the school service for the very first time with her chin held up high. She had spent the rest of the night pondering rigorously, and had absolutely no clue yet as to how she could bring Francesca to hurtle into a speeding auto, but she still knew she’d find a way. If she wanted something to happen, it would. Did action heroes cling to itineraries? Did they overthink strategies and stick to strict and unwavering protocol? No, they did not. Ploys like these unfurled best under pressure at the eleventh hour in the nick of time. She believed, despite everything, that there was justice in this world, and that vengeance for Lola Monina must be a thing of nature, spontaneous. Things would just click into place, she assured herself as she shuffled towards the Grade 4 wing. She could feel it. She could really, truly, really truly feel it.

Moments later at the principal’s office, Yna could hardly feel a thing.

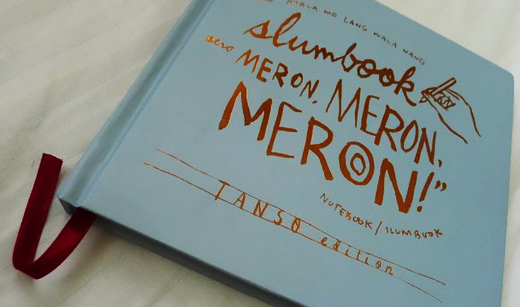

One part of her plan had worked out beautifully: Francesca’s yaya, while unpacking her ward’s lunchbag the previous day, had found the note. But Francesca’s yaya was not like Jobeth or Annabel or any of the help that had ever timidly tendered their services for the Santamarias. Francesca’s yaya turned out to have more gumption than Yna expected. Upon reading the note, she immediately rifled through Francesca’s backpack for any other nasty scraps that may have been planted by some villainous brat or other, and chanced upon Francesca’s slumbook.

Yna fidgeted upon mention of the accursed book. She felt herself weakening more and more as Francesca’s yaya, who was hunched across from her in the office, recalled her detective work with no trace of conceit, as if Yna had been a long foreseen disturbance. Francesca wasn’t even there. Her absence announced that she had better things to do than to watch an enemy fall. Yna pictured her at the covered courts for P.E. at that moment, placing a custom pink-and-white fencing mask over her ceaseless smile, knowing that her yaya was merely putting things to right.

The note, Francesca’s yaya explained as the principal, Ms. Violeta Consunji-Villufuerte, cracked the slumbook open to an earmarked page and held it right up to Yna’s face, was a perfect match in handwriting with one particular entry. Yna tried not to inhale the berry-scented sheets before her, but she could no longer hold her breath to the stink of her betrayal:

What is your favorite book: “The Little Princess”

What do you want to be when you grow up: Lara Croft

What is the best advice you’ve been given: My lola said always remember you are special.

What would be the one thing you’d change about yourself: none

What is your deepest fear: That we become very poor and my Mommy and Daddy become sick and die because we cannot buy medicines.

What is love: Love is blind.

Why are we friends: Because you are a kind and smart girl.

“What do you have to say for yourself?” Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte asked Yna, taking out the scrap of a threat and slapping it against the book’s pages, the identical handwriting spelling out line after line of blame.

Yna ran through all possible answers to this question as quickly and calmly as she could, and pared them down to two choices.

The first option was to deny the allegations. She could say that the matching scrawls were borne of pure and freakish coincidence. Moreover, she could say that she liked Francesca and would not have answered the “Why we are friends” portion, let alone touch the slumbook, if she harbored such hateful intentions. The latter, in particular, she knew she could deliver convincingly; in their history as classmates, she had never shown Francesca a smidge of ill will. Didn’t talk about her behind her back; smiled at her when they crossed paths to and from the washroom; was wholly cooperative when both were groupmates for Interpretative Dance, holding her hand with no trace of revulsion as they mimicked the surging surf that had beached a butanding in Batangas. There was no proof that she had disliked her beforehand. In fact, Yna knew that if she had asked herself outright, just for the sake of it, whether she did dislike Francesca or not, neither yes nor no would have served as an honest, immaculate answer. It was either she thought she did but felt she didn’t, or felt she did but thought she didn’t—whichever the day’s circumstances prescribed. What Yna was sure of was that Francesca had the right to be admired, and that, when it came down to it, she did hold a genuine morsel of esteem for her.

The second option: an appeal to pity. Kyra Tantiangco had gotten out of the previous week’s third quarter exams because her Senator dad and his mistress’s filmed foray into S&M was going viral, and the media’s hubbub right outside their gates made it hard for Kyra to study. All Yna had to do was confess something similar, something horrible yet factual and most definitely someone else’s fault, maybe do so with a crestfallen, world-weary look on her sweet, young face, and simply wait for understanding and forgiveness to commence. Yna didn’t mean to try and kill Francesca, she could foresee Ms. Consunji-Villuafuerte concluding. It was a cry for help, the poor girl.

The more she thought about it, the more appealing it seemed over the first option. People were very nice to children who had post-traumatic stress disorder, which was what Kyra told everyone she had the second she got back from her “healing week” at Shangri-La Mactan. If Yna couldn’t remedy her family the way she had planned, maybe this was another way. If her family believed that their woes had taken their toll on her, she would have to be given whatever she wanted lest her brittle, post-traumatic heart collapse in a quick, pained puff of dust, and this collective effort to ensure her welfare just might bring them all together, maybe stop their griping for once. Maybe if everyone would just stop scaring themselves and think, if they would just take it upon themselves to actually do something, something decent could happen.

“My Lolo Sixto is dead,” Yna began, sinking her gaze to the carpet, trying to look as tired as possible. “He died and he left us. I am so sad because he died. I cry all the time. My family is very sad also. We miss him so much and I wish he didn’t die. My mommy and my daddy and my tito fight all the time because my lolo is dead. We are very poor because my lolo gave all our money away and then he died. It is so hard to be poor. We do not have many things anymore. I am so scared. I am so scared that we will be poor forever and maybe we will not have food to eat and our clothes will have holes in them— “

At this point, Yna had bunched up her face as much as she could, hoping each strained muscle spelled an excruciating, undeserved sadness. Slowly, she glanced up at Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte, likewise hoping her eyes were twinkling with the threat of tears, expecting concern to glaze over the principal’s usual pallor. But she looked the same.

“—And I get nightmares all the time. I am so scared. I want to be happy. I want to be happy like my classmates. My heart hurts all the time. I remember my lolo and I miss him everyday. I miss the times when my lolo was alive and my family was happy. I am so sad. I want to stop being sad! I want my nightmares to go away! I want to be happy! I want to be so happy and I want my family to smile and laugh and love each other again like a real family! I want to be happy again! Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte, please help me! Please help me! I am so sad! Please help me be happy again!”

Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte closed the slumbook gently, set it on her desk, and clasped her hands on top of its glitter-coated cover with a strange finality. Yna slumped back in her chair. She felt that she had said her piece well enough. She couldn’t imagine anyone not feeling sorry for her—what she had just said was just so cheerless and so despairing and, when it came right down to it, tainted with just enough truth to make each word dense and firm. She looked straight at Ms. Consunji-Villuaferte with unblinking anguish. The principal rolled her eyes.

“The Canterbury International Grade School of Alabang is committed to the inculcation of the finest intellect within the minds of the most reputable young ladies in the nation,” she replied. “While we would like to envision each and every one of our wards—including you, Ms. Santamaria—to be of superior mental prowess, you must never forget to foresee the same of this institution’s pedagogues and administrative body. I am not an imbecile. It is no secret that Mr. Sixto Santamaria, just days before his decidedly unfortunate demise, exacted a very severe and mysterious case of philanthropy that has left his kin sinking slowly but surely into poverty or, at the very least, the throngs of the middle class. Mr. Santamaria was a most esteemed Filipino businessman, with Santamaria Sweets being one of the oldest and most firmly established brands in the nation, so it should most certainly come as no surprise whatsoever that the public had caught wind of his bizarre pre-death wish. I comprehend that your life at home may be quite conflict-laden because of this, and that you may be feeling much grief and uncertainty towards the future, but neither this, nor anything else, can be seen as grounds for your atrociously poor plans to endanger your fellow Canterburian Ms. De Dios. What good did you think would come of this slovenly attempt at underhandedness, Ms. Santamaria? A handwritten threat? A maudlin soliloquy about domestic stress to defend it?”

Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte sighed, and the fury in her stare then cooled to a stern, steady sizzle. This slight change, however, made Yna more agitated than she already was, for it seemed that the principal was set to wield something far worse than rage: her pure and pitiless authority.

“I may not know exactly how repugnant your home life presently is,” she continued at a more level, professional tone. “But I do know that your plan to harm the De Dioses was not of exceptional quality, and that this cannot be pardoned. This is the crux of your problem, Ms. Santamaria. In fact, your plan merited no quality in any way. It did not meet this institution’s high standards. Have you no pride in your schooling, Ms. Santamaria? Have we taught you nothing about revenge? I have appraised the coursework you have fulfilled since Prep 2—Introduction to Warfare, Junior Business Negotiations, the Holocaust Primer, among other subjects. One would think that all this knowledge would have enriched your transgressive little endeavors. But, in your particular case, they have not, despite the fact that you do possess enough of an intellect. So what is the reason behind your failure? It is because you do not try hard enough. You have only willed yourself to exert the barest minimum of effort, when a Canterburian truly worth anything would have invested her entire being into destroying her enemy. You see, Ms. Santamaria, only passionate and disciplined people succeed throughout history.”

Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte then let out a tiny, tired puff of air from her lips before resuming.

“This is why your family has fared the way it has. They did not exert the optimal amount of effort into bettering their state since Mr. Santamaria met his Maker. I do not know how it was, exactly, that your family tried to boost their earnings in your grandfather’s glaring absence, but I do know—I believe everyone knows—that whatever it was was far from satisfactory. So please do not hold your family—or absolutely anything else—at fault for your own disappointments, because neither can your family reproach anyone but themselves for their aggravations.

“It is no surprise that De Dios Farms is acquiring Santamaria Sweets by the end of the week. Now, do not stare at me like that, Ms. Santamaria. The decision was declared in the broadsheets this morning, so please do not feign your ignorance of this matter. Or were you truly not informed? In hindsight, that seems to make sense; your kin would have liked you to maintain your delusions, I feel. Anyway, as I was saying, just as your family should have stood up for themselves more intensely, so should you have sought retribution with greater fervor. Were you planning to use Ms. De Dios as actual collateral? Swap her for Sweets? Or were you more for attacking her family’s psyche? Break them down from the inside, perhaps? Whatever it was, Ms. Santamaria, the fact remains that you have proven yourself futile, and that the De Dioses have proven themselves to be the much, much better lot. They won, Ms. Santamaria. They beat you. They did what they had the very best way they could, and I do not care if that grimace of yours says otherwise, Ms. Santamaria. They beat you. And you lost badly.”

As Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte went on to the details of Yna’s penance—a three-week period as barista at Canterbury’s student café during lunchbreaks, and additional coursework on Quantum Mechanics for the rest of the school year—Yna glanced at Francesca’s yaya, who had not spoken or moved or quite possibly respired during the principal’s homily, and saw in the crone’s gristly face for the very first time a tinge of contentment, maybe joy. It was an unsettling, yet not unnatural, expression, and Yna could feel it directed at her deliberately.

She supposed she deserved it. If she were Francesca’s yaya, she would have shot the poor girl before her with the same, self-satisfied look herself. There was a truth that was hovering around them at that moment, calmly humming the refrain about Yna and her stubborn reluctance to believe in herself. It was one of those familiar tunes that had always loitered in the backdrop of her life thus far, ever-present yet only faintly heard, and although this sound could be readily ignored, she always strained to hear it all the same. The odd wisp of a smile on Francesca’s yaya’s face, she realized, meant the yaya could hear it, too.

Yna did not look away from her, provoking a little staring match between them. Not surprisingly, Francesca’s yaya was very good at it, as if her look was really meant to endure, as if she were tasked to actually tell Yna something more specific and was just building tension for a more distressing reveal. Or, in contrast, perhaps Francesca’s yaya knew something staggering that she was forbidden to tell. Either way, Yna had a notion that she should be more upset than she already was.

Lola Monina suddenly came to mind. She looked back on the old woman’s nightly ambles, those dead-silent, stretched-out strolls around and around the Santamaria’s turf and the normally empty piece of street in front of it. She would neither glance about in search of something, nor touch things with the faintest fondness, but it was that very vacuity in her movement—traveling in straight lines; turning at sharp angles; looking coolly ahead—that made these walks seem so disquieting. They started shortly after Lolo Sixto passed away, and Lola Monina seemed to have kept the habit unbroken up until her brush with the treacherous truck. Yna would watch her from her bedroom window most nights, slightly startled and spellbound by it, being so typical a sign of lunacy as it was, but never expected it to do the old woman more harm than it actually had. During the only occasion when she was asked by Yna about her walks, Lola Monina replied, and with much exasperation, To get an idea. And whatever that idea was—Yna had wondered about it feverishly for a time but gave even that up just as fast—it probably wasn’t supposed to be in the form of a speeding truck.

This led Yna to have ideas of her own. After all, a De Dios farms truck careening down the streets of their gated village at the dead of night didn’t have to be so damningly arbitrary. Why all this say-so that it was an accident? Then again, even if it wasn’t an accident, what did that morsel even matter? How worthwhile would it be for her to speak up about her suspicions, to point a steady finger at the true felons, to give her heroics just one more gracious go, after she had just been christened a catastrophe?

“You may join your peers for recess, Ms. Santamaria. And thank you, Lucy. I extol your prudence.”

Francesca’s yaya rose from her chair, gave Mrs. Consunji-Villafuerte a curt nod, and headed towards the door.

Yna, on the other hand, stayed put, suddenly upset that that moment—that room; those stares; that pungent, accusatory air—had to be wrenched away from her, because she was certain that the longer she stayed, the safer she would be amidst the room’s wall-length bookcases in the darkest dark wood and its thick, blood orange carpet, and Mrs. Consunji-Villafuerte’s frigid, focused demeanor. There, there was still a chance for something to develop, some sudden brilliance or flare of courage in her that would propel her to try and change her principal’s mind. Maybe, if she waited long enough, she could muster up a way to speak up about Lola Monina and what could have very well been the dastardly plot to exploit her. She wished she had brought it up earlier on, although something had also been blurring or muffling it at the time, as if sheathing the subject in a thick smock of smoke. She watched Francesca’s yaya open the door, wincing a bit as the thing swung inward, as if this had let some rare and precious creature escape.

But there in the receiving area was another rare and precious creature of drastically different specie, its back steel rod-straight, its feet twirled primly together and tucked back at a ladylike angle. It was eating from a packet of De Dios Dried Mango Strips, nibbling at one gnarled, dark yellow piece with relish, as if nourishment was a hobby it dabbled in at idle hours. It was this correctness that the Santamarias craved, this immunity to the world’s strains. The creature seemed to have no qualms sitting there, as if being told to snack in the principal’s receiving area instead of with the children in the gardens was nothing to be worried about. Because it wasn’t; whatever the De Dioses did, they did it without fault. They feared nothing.

“Please leave my office, Ms. Santamaria.”

Yna pretended not to hear Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte. At the very least, she would wait until the figures by the doorway had left before attempting to peel herself from the chair. She had determined the creature to be dangerous, and preferred not to risk corrupting its space. In a way, it was even a little bit nice to be staring at it from a distance, far enough as she was not to provoke it, yet just close enough for its raw might to be palpable. It was then that Yna recognized how powerless she was before it, and how fruitless her hopes to harm it had been from the start.

Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte rose sharply from her chair and walked up to Yna, who continued to ignore the woman now glaring intently by her side.

“Please leave, Ms. Santamaria!”

By this time, Ms. Consunji-Villafuerte’s ire had lost nearly all of its potency for Yna. The little girl merely gripped the chair’s backrest doggedly and kept gawking at the exquisite scene before her.

As the yaya adjusted the face towel bunching at its nape, the creature continued to feed. It bit into each morsel slowly, leisurely, chewing with much patience, looking so pleased at that moment, as if it had been served a costly delicacy for the very first time in its life.

Yna then stared at the small pieces of food being brought to its lips—these knotty, dulled little things—and realized that she had never tried them. She had never experienced these perplexing fragments of fruit, like shriveled specters of their old, succulent selves. She wondered what they must taste like, sliding her tongue bit by bit across the inside of her lips, closing her eyes for an instant and willing her mouth to water.

She thought about it hard. She thought of something sweet.

—-

Marguerite Alcazaren de Leon is not sure if she will be employed by the time this story comes out. Nonetheless, her priorities remain with her fiction, the Filipino Freethinkers, and preventing her apartment from falling into squalor.

Witty Will Save The World, Co. sells the above, very witty, slumbook. Image is from here.

This story was first published in the Philippines Free Press in 2010.

cheers for posting, great content – Calum